By Christopher Campbell-Duruflé

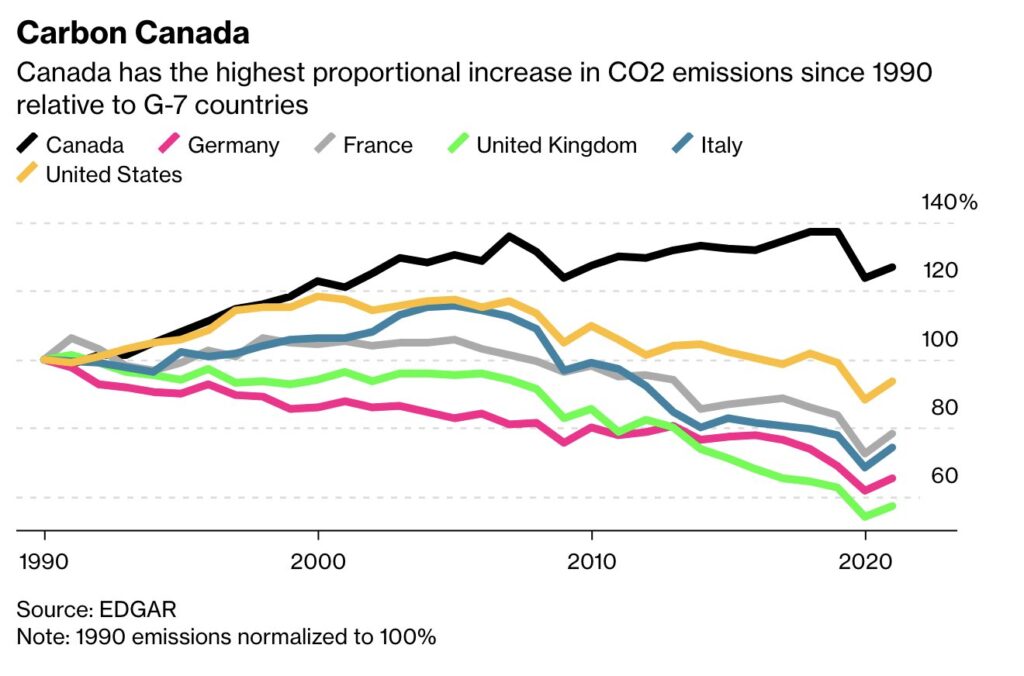

Canada was an early supporter of the Paris Agreement, adopted at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2015. The Prime Minister famously declared on the eve of the negotiations: “Canada is back, my friends. Canada is back, and here to help”. Seven years later, as state delegates meet again from 6 to 18 November 2022 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt to monitor the Agreement’s implementation, whether Canada is still back is a question that looms heavy. As recently reported by Bloomberg Green, our country had the highest increase in CO2 emissions since 1990 in the G-7 and its per capita emissions are second only to Saudi Arabia within the G-20.

These trends jar with Canada’s latest pledges under the Paris Agreement, namely to reduce yearly emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) between 40 and 45% below 2005 levels by 2030, and to reach net-zero by 2050. At the 2005 baseline, our emissions were at the all-time high of 739 Mt of GHG. This equates to 739 million tons of CO2 equivalent, or roughly 739 million one-way flights over the Atlantic by one person that year alone. By contrast, Canada has pledged to reach 440 Mt in 2030 and then to continue decreasing, rapidly, to reach net-zero by 2050.

One may wonder how the notion of “net-zero” differs from “zero” emissions. The Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act defines net zero in Section 2 as meaning that any remaining emissions in 2050 could be “balanced” by removals from the atmosphere. Put simply, a removal can happen either by expanding natural carbon sinks such as Canada’s forests and wetlands, or by using technologies that can capture carbon from the atmosphere, most of which are still under development.

Canada’s poor climate performance and reputation as a “climate laggard” raise three questions with regard to how this country approaches net-zero.

- How many tons of GHGs are we really planning on emitting in 2030?

Is Canada planning on emitting 440 Mt for that year alone, or are we bracing for more and hoping to balance exceeding emissions with removals by natural sinks and carbon capture technologies? How much more? Canada’s latest pledge under the Paris Agreement includes a projection of 468 Mt in 2030. This suggests that it will be necessary to remove 28 Mt that year alone if no new mitigation policies are introduced.

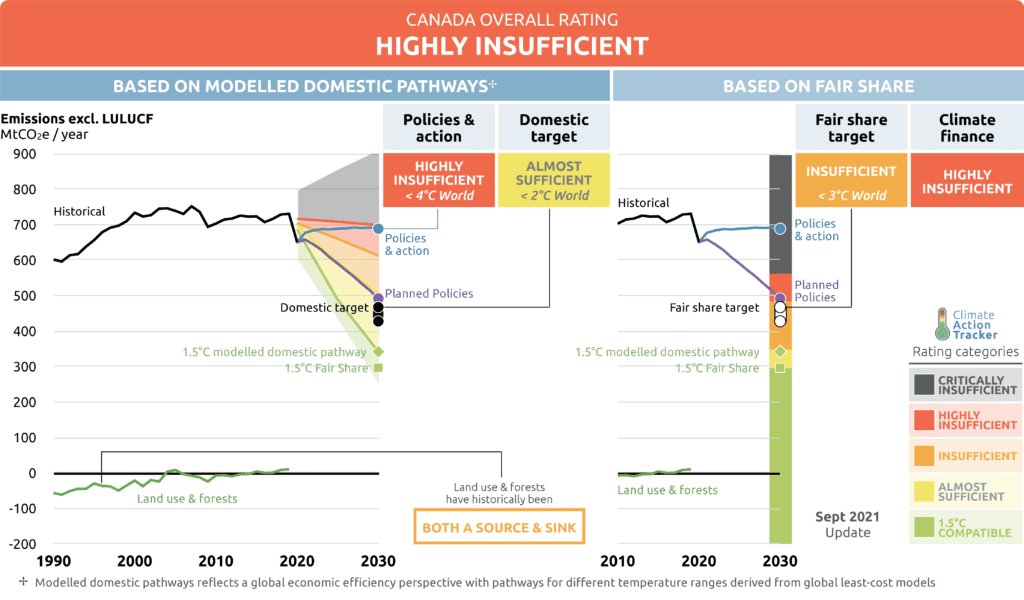

Yet certain assessments are even more pessimistic. In 2021, Climate Action Tracker rated Canada’s policies and action as “Highly Insufficient” to achieve its targets. This independent research organization also warned that emissions in 2030 could be as high as 688 Mt -opening up a vertiginous gap of 248 Mt.

2. Will Canada fill the domestic action gap with new policies and actions or by purchasing emissions removals from other countries?

The Paris Agreement allows a country like Canada to purchase emissions removals achieved in other countries and to deduct these from its own inventories. Specifically, Article 6(2) allows countries to purchase emissions removals from one another and Article 6(4) deals with corporations purchasing removals to offset their own environmental impact.

In 2022, the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan: Canada’s Next Steps for Clean Air and a Strong Economy confirmed Canada’s interest in purchasing GHG removals from other countries. The plan does not indicate, however, to what extent this option will be relied on to reach 440 Mt in 2030:

While Canada’s actions to date have focused on emissions reductions measures within Canada, there is also the potential to support international action through ‘internationally transferred mitigation outcomes’ (ITMOs). ITMOs offer the possibility of emissions reductions at a lower cost, while contributing to sustainable development abroad. The Government of Canada will continue to explore the possibility to leverage international and domestic offsets to support Canada’s climate objectives. (p. 99)

I argue that greater clarity is needed regarding how Canada intends to fill the domestic action gap. Under the Paris Agreement, purchasing emissions removals is not meant to allow countries to coast on emission pathways that would lead the world to 4 °C of warming and to purchase their way to net-zero. Article 6 is meant to foster ambitious action through international cooperation and, under the rules adopted last year in Glasgow, Canada will have to report every two years on how purchasing removals contributes to achieving the Paris Agreement’s goals. My hope is that we seize these occasions to have public debates about how much Canada intends to rely on other countries to reach 440 Mt in 2030 and net-zero in 2050.

3. Will Canada avoid funding projects that harm local communities when purchasing emissions removals from other countries?

The very notion of purchasing emissions removals from other countries raises major challenges. The recent Land Gap Report warned that the land necessary to satisfy all countries’ current climate pledges under the Paris Agreement amounts to 1.2 billion hectares. This area equates to the totality of the world’s cropland and using it for reforestation and other forms of land-based removals would seriously compromise global food security.

Multiple projects linked to the international purchase of emissions under the Kyoto Protocol have attracted criticism for causing human rights violations, often in the context of land disputes with local communities. These projects include the Aguan biogas recovery from a palm oil mill project in Honduras, the Olkaria IV geothermal power project near Maasai villages in Kenya, and the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam in Panama. In this last case, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples observed that the project promoters did not adequately consult the Ngobe-Bugle Indigenous people, as a result of which at least two members were killed and women were raped during demonstrations in 2012. Yet, the project led to the sale of over 66,000 tons in emission credits that were purchased internationally for approximately USD 12,000.

Many proposals were made to prevent this problem from continuing under the Paris Agreement. Regrettably, negotiators only agreed on creating a weak right to appeal decisions of the Supervisory Body in charge of monitoring the international purchase of emissions based on Article 6. Amnesty International warned that a scheme devoid of sufficient environmental and human rights safeguards amounts to a “hollow and unacceptable substitute for real zero emissions targets.”

In this context, I argue that Canadians have a heightened responsibility to ensure that any international purchase of emissions removals (by governments, corporations, and individuals) does not fund projects that violate human rights, displace Indigenous peoples from their territories, and sidetrack sustainable development in host countries. Again, the federal government will have to report biennially on how its purchase of emission removals minimizes environmental, economic, and social impacts. It is up to all of us to demand that Canada repudiate any form of carbon colonialism.

Canada will be at COP27, well represented by its Environment and Climate Change Minister, its Ambassador for Climate Change, parliamentarians, and civil society organizations such as Indigenous Climate Action. But is Canada still “back” in the way it appeared to be in 2015, as a trustworthy negotiation partner that would follow through on its international commitments? Greater clarity regarding how Canada will reduce its emissions to 440 Mt in 2030, limit its reliance on the international purchase of removals to a strict minimum, and prevent adverse impacts on global food security and local communities are basic conditions that remain to be satisfied.

Christopher Campbell-Duruflé

Lincoln Alexander School of Law

Areas of Expertise: International law, environmental law, human rights, climate law, Inter-American human rights system, sustainable development, international relations

Assistant Professor Campbell-Duruflé teaches class actions law at the Lincoln Alexander School of Law. His research focuses on the role of international law in responding to some of the most pressing challenges of our time. He has published on the negotiation of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, appeared before the Senate during the study the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, and supported discrimination and Indigenous rights litigation within the Inter-American system. He is a Fellow of the Cambridge Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance (C-EENRG) and a member of the C-EENRG Research Series editorial team, and serves on the legal committee of the Centre québécois du droit de l’environnement.